Preface

Hello! This guide is meant to serve seniors in the DPEA in the software division. As you go through them, keep in mind that they were all made by fellow DPEA students, so there will most certainly be errors. If you catch one, submit a pull request to the softdev-training repository on Github (one of these pages will teach you how to do so!) to improve documentation for all.

Linux and the Operating System

Before we delve into the specifics of learning programming languages and algorithms, it helps to know how the computers you work with everyday work, why they operate a certain way, and how you can manipulate those operations to do what you want. After a brief overview of Linux as a whole, we’ll get into an introduction into the command line and its many processes.

The History of Linux

As you might know, Linux is an operating system, or the glue behind all of the chips and circuitry inside of your computer. Currently, the DPEA workstations (what you’re likely reading this on) are running off of Ubuntu, which is a user friendly flavor of Linux. There are many different types of Linux flavors, from Kali Linux to Debian to Fedora, all of which are unified under the fundamental Linux kernel. It was rooted in the UNIX operating system, developed by Ken Thompson and Dennis Ritchie of Bell Laboratories in 1969, and continued by Linus Torwald in the modern era. The swaggy king himself is shown below:

What does Linux do?

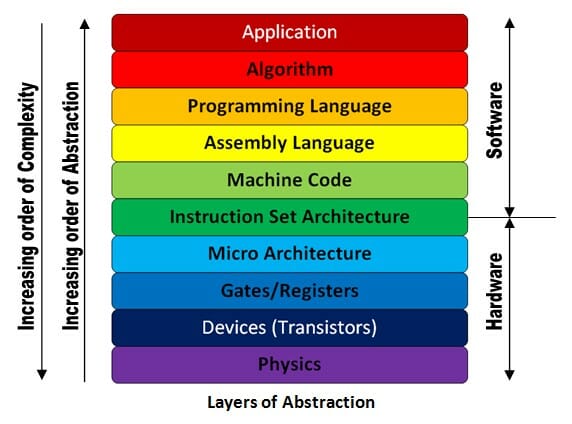

The beauty of the Linux terminal is that it connects underlying hardware with software, running your device, peripherals, and more. It’s reliant on abstraction: it clumps things up into fundamental building blocks – command line utilities – and builds upon those command line utilities to run code and manage resources. For instance, the layers of abstraction in a computer is shown below:

By directly accessing these command line utilities, we can do some really powerful stuff with the amount of control we have over the system. To do so, we need to explore the command line.

The command line

What is it?

The command line is a method of directly accessing system utilities through text. They allow us to quickly and easily manipulate system resources and activities, which makes them super useful when it comes to writing code. Let’s go through some basic Linux commands together – try and follow along in your own terminal, which you can open through that gray box with a >_ icon within it. This is shown below:

We’ll be using bash, which comes as a default on most Linux systems.

if this is your first time with a terminal, I’d highly reccomend you follow along and play with some of the commands as well! It’s tough to learn things by just reading through documentation, but being able to see your computer interact with commands and troubleshooting those interactions is a great way to learn all of this content.

echo

The most fundamental command in the Linux terminal – whatever you pass in, it spits out. Try out this:

echo hello world

Congrats! You wrote your first bit of command line code! Your screen should look something like the image shown below.

pwd

Alright, let’s start exploring your computer through the command line! Your computer is centered around directories, also known as folders, in a hierarchal tree. For instance, this is a rough example of what a directory looks like:

├── bin

│ ├── file1

│ ├── file2

├── home

│ ├── file3

│ ├── alokthakrar

│ │ ├── file4

│ │ ├── file5

│ │ ├── images

│ │ | ├── kermit.png

│ ├── file7

├── etc

├── apt

The location of an individual file in this tree is called its path. The path just specifies the folders you have to go through to get to a specific file: For instance, the path /home/alokthakrar/images/kermit.png would mean you have to go through the home folder, then the alokthakrar folder, then the images folder to get to the file kermit.png.

It’s helpful to discuss the working directory in the context of the terminal for this. In our case, the working directory simply means the folder you’re currently in, and can thus operate on in ways we’ll see earlier. Directories are the same things as folders, though they do feel cooler to say and are used much more in programming contexts, so you’ll see them interchangably in these documents.

You can tell what folder you’re in, or see the working directory, through the command pwd. Try it out on your terminal! You should recieve something that looks like this:

/home/softdev

Pretty cool, right?

ls

We know where we are… what’s around us? The ls command is here to help us determine that.

Try typing in ls in your filesystem! You should see a list of folders around you. For instance, looking back at our filesystem above, if we were in the folder alokthakrar, we would see file4, file5, and the images folder.

Cool! One other thing – if we add flags to our commands, we can do even cooler stuff! For instance, ls -a makes hidden directories visible, ls -l makes the output much more verbose, and you can combine these flags together – ls -la – to combine their effects. This also works if you seperate out your flags: e.g. ls -l -a

Flags that are single letters are added on using a single dash: e.g. -a, but with other, multi-character flags, you need to add a double dash: --all, for instance, which has the same fucntionality as -a. for the ls command. If this doesn’t make sense, don’t worry! we’ll cover the concept again in the man page.

cd

We know where we are, we know what’s around us… how do we move around the filesystem? cd is the answer!

Let’s first clarify paths a little bit. There are two types of paths: Absolute paths and relative paths. Absolute paths start at your root directory, or the directory at the very “bottom” of your computers’ file structure, and tell you how to navigate to a given file. The root directory and absolute paths are typically signified with the path starting with the “/” symbol.

Relative paths, on the other hand, start at your working directory (the folder you’re in). For our above filesystem: If I’m currently in the /home/alokthakrar folder, a relative path would be images/kermit.png, and as there’s no slash it indicates tells the console to treat the path like the absolute /home/alokthakrar/images/kermit.png. It’s a sort of strange concept, but hopefully it’ll become intutiive after some rereads (and some trial and error on the console) Note that this process is implicit, but you also can manually specify the working directory with a .: e.g. ./images/kermit.png, though that takes extra time and programming is often about being lazy.

cd allows you to pass in a path to change into. First, try and look at what’s around you using ls: for instance, I have the “Downloads” folder, among others! Now try:

cd <folder name to change into>

For me, that’d look like:

cd Downloads

Paths are case sensitive: cd downloads errors out, while cd Downloads doesn’t.

Now: see how your environment has changed! Try an ls and pwd and check out the output: these should be different.

What this is doing is using a relative path to be able to tell the console to navigate to the downloads directory. In essence, it’s telling the console under the hood that you should change into /home/alokthakrar/Downloads, but as our working directory is /home/alokthakrar there’s no need to specify that in our path. Just to be clear: cd /home/alokthakrar/Downloads would have the SAME effect as cd Downloads, one is just a lot easier. Note that this pathing scheme is applicable for ALL terminal operations, which is very useful.

This is the most straightforward, and honestly the most applicable way of using cd. All you need to do is find what folder you want to navigate to, and cd into it.

You also can navigate into your user profile’s default directory by just typing in cd, with no additional arguments. That’ll take you to the filepath where you start up your terminal in. For me, that’s home/softdev, as that’s the name of my computer. Try it out!

Play around with this! Try and navigate through to different folders! Some examples you can try:

-

Navigate to the images directory!

-

What do you think

cd /does? Where does it take you? What will be the output of pwd? -

Try and change directories using absolute pathing!

-

Can you navigate through multiple directories in one sitting using cd? How?

One thing you may have noticed: it’s really difficult to go backwards a directory using cd! That’s why there’s a handy shortcut: cd .., which changes directories into the parent folder. Note that .. just referes to your parent folder. For instance, if I was in /home/alokthakrar, cd .. would take me to /home. This can be chained: cd ../.. from home/alokthakrar/ would take you to / (your root directory), and cd ../../opt from that same working directory would take you to /opt. You make a chaneg Two other shortcuts to mention are cd ~, which defaults to your home directory (same as cd with no arguments) and cd -, which takes yuo to the directory that you were just in.

These commands are the fundamental building blocks of terminal operations. I’d reccomend playing around with them a little bit, as having an intuition for them is really helpful! Below are other useful Linux commands, that, while useful, are likely going to be less essential than something like pwd, cd, and ls. I’ve listed some of the most pertinent ones in a rough order of importance. I’d advise having familiarity with them, as they are very helpful [and help with building intuition of using the terminal!] but there’s no need to become a mkdir master, as you’ll very rarely need to use it.

There’s an autocomplete feature on the terminals: if you type in a portion of the filepath, and there’s no other possible filepath that the given text could eventually be, you can autocomplete the rest of the folder name that you’re going to enter. For instance, tabbing after cd Do would give you a list of all folders you can navigate into that start with “Do” – in my case, both the Downloads and Documents folder, but cd Dow only corresponds to one folder on my system, Downloads, and would autocomplete to the full directory name. I’d play around with this feature as well. Autocorrect exists for all commands and paths.

touch

Make a new file. touch kermit.py creates a new file named kermit.py. touch Downloads/kermit.py works if Downloads exists. You can add a space in the file name with quotes: touch "Mr. PZ", for instance

cat

Print out the contents of a file. cat kermit.py prints the contents of kermit.py. Can specify multiple files: e.g. cat kermit.py second.py to concatenate them together.

cp

copies a file from argument1 to argument2, where arguments are the inputs passed into the command. cp kermit.png /bin creates a copy of kermit.png in alokthakrar, assuming kermit.png is in our working directory/scope.

rm

Remove files. rm kermit1.png deletes kermit1.png, assuming it’s in the working directory. rm -r directoryName allows you to delete directories, as well as the rmdir command, e.g. rmdir directory.

With great power comes great responsibility! rm is dangerous. If you delete the wrong folder, you can’t bring it back, and could potentially brick your entire computer.

man

Learn more about what a command does and its flags: e.g. man ls

Ctrl-C

Not technically a command, but to kill any running process (in this context, any command), just hit Ctrl-C. This is helpful if you have a piece of code that doesn’t terminate, but you want to stop.

mv

Same functionality as cp, just moves the files instead of copying them. mv kermit.png /home/alokthakrar moves kermit.png to alokthakrar.

mkdir

The touch for directories. mkdir PZ creates a directory named PZ.

clear

clear clears the terminal.

vim

The text editor for all of the cool kids. It allows you to edit files within the terminal, which is super useful for when you don’t have a GUI handy Vim is very helpful, but also is hard to use, so I’d only reccomend trying to learn it if you enjoyed the process of working in the terminal. I’d reccomend going through a guide like https://opensource.com/article/19/3/getting-started-vim, and avoiding emacs at all costs

sudo

Allows you to run commands as a superuser, or as someone with all available permissions. For instance, sudo ls will run ls as a superuser. Can save you if things break, though installs with sudo can also break things further. It’ll prompt you for a user password where no text will appear when you type – don’t be alarmed! If you type in your password and hit enter it’ll work as intended.

Conclusion

Congrats on finishing the first page of the DPEA softdev training! Hopefully it was somewhat of an enjoyable experience, and you gained familiarity with using the terminal. Though this may seem tedious, the terminal is exceptionally useful in almost all STEM fields, as many are incorporating computing within them, so it definitely is a good thing to learn about regardless of your future profession. It also makes troubleshooting things at the DPEA a lot easier :)